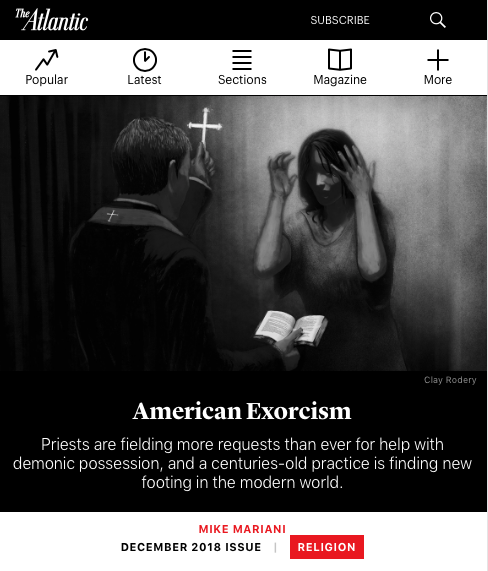

Exorcism feature article in December 2018 issue of The Atlantic

The Atlantic features Exorcism — December 2018 Issue

There has long been a relationship between plurality and possession. In this month’s Atlantic, there’s an article regarding the resurgence of exorcisms, the religious antidote for demonic possession. Be advised there’s some pretty graphic descriptions of spiritual/religious experiences and potentially more in the article.

Whether you believe in a religion that demonizes plurality, or you believe in spirituality or not, and aside from the potentially possessed person who is featured in the story, the fact is that many exorcists are experiencing an extreme uptick in requests for exorcisms which gives rise to the question of whether any other alternatives are being considered before people turn to eviction as a solution for their potential headmate problems.

Why, in our modern age, are so many people turning to the Church for help in banishing incorporeal fiends from their body? And what does this resurgent interest tell us about the figurative demons tormenting contemporary society?

To their credit, according to the article, priests are supposed to first do something resembling a differential diagnosis:

Catholic priests use a process called discernment to determine whether they’re dealing with a genuine case of possession. In a crucial step, the person requesting an exorcism must undergo a psychiatric evaluation with a mental-health professional. The vast majority of cases end there, as many of the individuals claiming possession are found to be suffering from psychiatric issues such as schizophrenia or a dissociative disorder, or to have recently gone off psychotropic medication.

Unfortunately, there’s still major overlap with abuse victims and potentially dissociative disorders:

Nearly every Catholic exorcist I spoke with cited a history of abuse—in particular, sexual abuse—as a major doorway for demons. Thomas said that as many as 80 percent of the people who come to him seeking an exorcism are sexual-abuse survivors. According to these priests, sexual abuse is so traumatic that it creates a kind of “soul wound,” as Thomas put it, that makes a person more vulnerable to demons.

The main interview features a person whose childhood history would be familiar to many who have had C-PTSD and a childhood full of trauma. Some of the “possession” incidents sound hauntingly like dissociative episodes for someone with dissociative identity disorder (DID).

In a moment of reviewing the similarities of DID and demonic possession the article states:

No lab test can pinpoint the medical source of these types of mental fractures. In one sense, the blurry shadow-selves that surface in what we call dissociative states and the demons that Catholic exorcists believe they are casting out are not so different: Both are incorporeal forces of ambiguous agency and intent, rupturing a continuous personality and forever eluding proof.

It’s obvious that article-writers, counselors, and priests alike may need to hear of more forms of plurality to understand new potential ways to address these others within the group entity they are addressing.

The article ends with ambiguous non-resolution for the featured tormented person. She is still having problems in spite of religious interventions. She has not been exorcised as of the close of the article.